Composition underpins all artworks and is the essential framework that they are enhanced by and cannot exist without. It refers to the arrangement of visual devices through line, shape, and space to create harmony and contrast. When made successfully, a great composition will guide the viewer’s eye to enhance narrative, and help to convey the intended emotional response to the work. Making conscious decisions on how different elements of an artwork interact with each other is key to the artist’s vision, whether that is achieved through mathematics or spontaneity.

Madonna of Mercy, 1440s

Sano di Pietro

Composition Throughout Art History

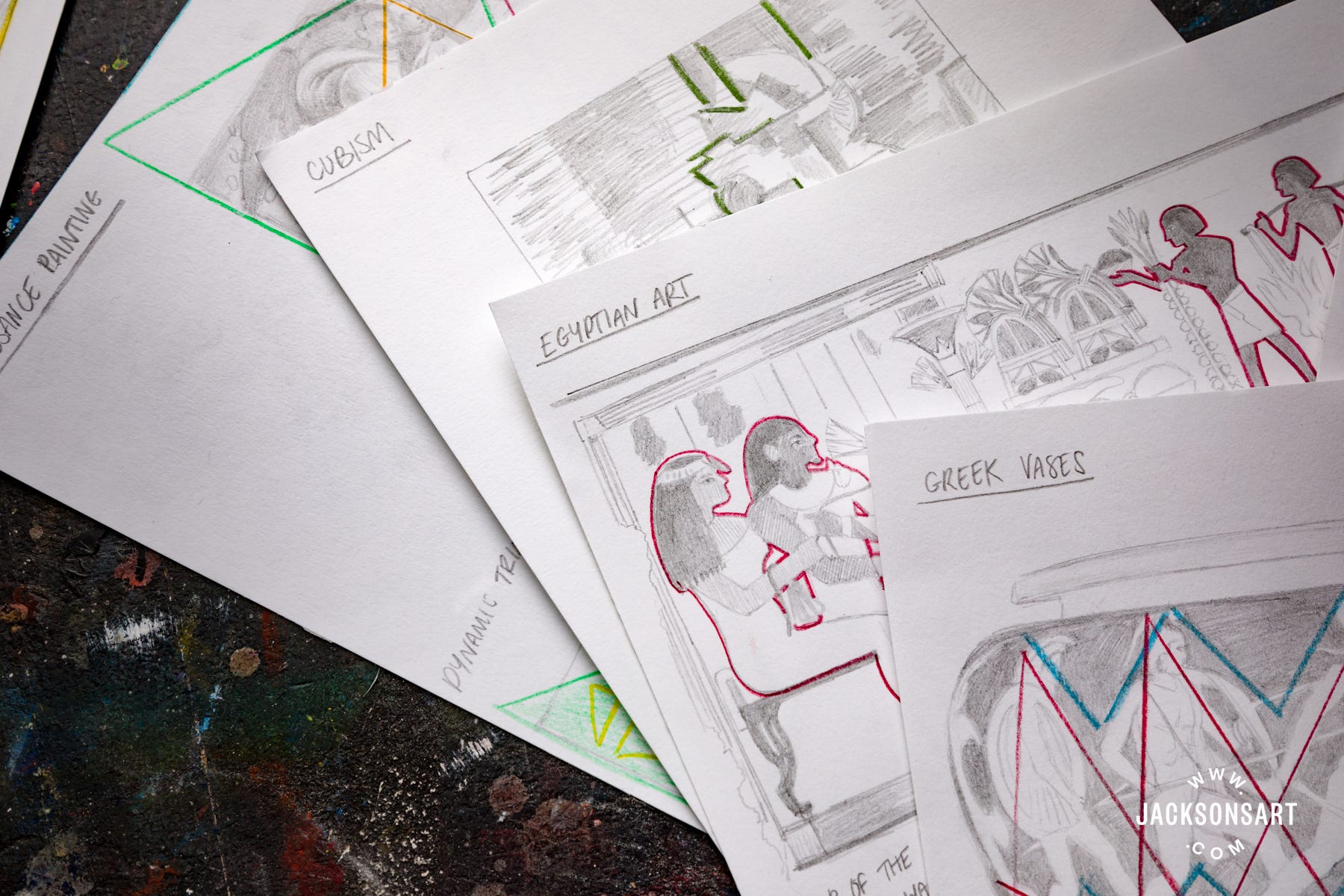

Throughout time, tastes in composition have evolved within art historical movements. Here I will detail some key compositional breakthroughs from a selection of these. Recognising the principles that the artists of the past were faithful to in their work offers an exciting opportunity to explore how these approaches could be adapted into our own vision.

Visual Hierarchy – Egyptian and Medieval Painting

Egyptian Art is instantly recognisable by its highly stylised and symbolic iconography, which reflects the beliefs and social structure of this ancient society. This is directly mirrored in the use of visual hierarchy, where figures of importance – be they the Gods or ruling humans – are made the biggest. In turn, the characters of lesser significance are made smaller. These are arranged across strict horizontal compositional guidelines, designed to convey order and eternity. The works don’t intend to be representational of the people involved, but signify their status and the narratives of their lives and mythology. Interwoven with hieroglyphics, these images are created to be ‘read’ in a literal sense.

Drawing of the composition of the North side of the West wall of Nakht’s Offering Chapel (1410-1370 BC).

I have extracted my example imagery from a tomb wall for an Egyptian official named Nakht and his wife Tawy. They dominate the fragment in scale on the left. In declining size order as we move across, we see their workers presenting the harvest to them, and preparing wine. The idea of conceptual hierarchy of importance can also be seen in Medieval paintings, where figures like Mary may be the largest, with human worshippers surrounding her in miniature, such as in the Madonna of Mercy (1440s) by Sano di Pietro.

Triangular Repetition – Ancient Greek Pottery

The Ancient Greeks made incredible pottery, with dynamic scenes of war and heroism wrapped around their surface. Although constrained by the boundaries of a horizontal ‘bar of action’ that wraps around the pottery, these images are full of movement. This is largely due to the repetitive triangular composition they employ, where the position of the figures forms a zigzag that keeps our eye bouncing around the surface. The negative spaces around the figures also form triangles, due to the closeness of the edges of the horizontal space. The sharpness of this choice also emphasises the speed of the moment, despite being static, and potentially the violence being depicted.

Drawing of Red-Figured dinos (mixing bowl) with Combat of Attic Heroes with the Amazons (440-430 BC).

In the example I’ve chosen, we see a scene of combat between the Attic heroes and the Amazons, where Theseus strides forward sword in hand to attack the fallen Andromache. Our eye is driven forward with the triangles created by his legs overlapping with the warrior behind him and the fallen. This makes the scene feel frenzied and urgent, dynamic but stable, to emphasise the storytelling.

Dynamic Triangles – Renaissance Painting

It’s common knowledge that the Renaissance represents a leap forward in the development of visual art, through the use of linear perspective, the golden ratio, and advances in representational art through the study of anatomy. It’s clear that these advances were made through intensive study and mathematics, and followed loyally upon an intensively taught framework in their ateliers. There is simply too much to say about this era of art and its compositional advances in brief terms, so I will focus here on the use of triangles in their paintings.

In Renaissance painting, triangles create harmony, establish hierarchy, and reinforce stability. In The Birth of Venus, Botticelli created a triangle around the slightly off-centre Venus, with her head at the apex, and a solid base stretching along the bottom of the frame. The figures on either side of Venus reinforce the triangle, as exemplified by the red line on my drawing. The figures to the left, Zephyr and Aura, form a triangle themselves as they blow towards her, pointed toward her face. As does the figure on the right, Thallo, with her outstretched arm and stride. This arrangement of triangles towards Venus emphasises her central, divine presence in the work, as well as power, as the literal head of the biggest triangle we see.

Drawing of The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (1485-1486)

Within the work, there are further triangles to discover, which I have highlighted in yellow. These smaller triangles help to direct our eye around the work and create a scattered constellation that continues to direct our eyes around the entire surface. We can see a brilliant parallel between the placement of the knee on the left aligning on a horizontal axis to the bent elbow of Thallo to the right. Which, when connected downwards, creates another series of triangles that seem to provide Venus with a sense of movement upon her shell, despite her stillness. The contrast between the dynamism of these figures and their triangular arrangements, and the absolute serenity of Venus’ composure aligns with the themes of the work. It plainly emphasises the control held by the Gods amongst the chaos they may create, and the connection between nature and the divine.

Unlike the Egyptians, importance isn’t signified by scale, but more subtly by a structural undercurrent that we subconsciously recognise. Beyond the Greek use of triangles in their pottery, these Renaissance triangles no longer rely on bouncing along the edge. They exist within and break beyond the constraints of the canvas, giving them greater narrative freedom.

Balance and Space – Chinese Ink Painting

Traditional Chinese ink paintings are renowned for their balance and serenity, embodying beauty and harmony. Although often asymmetrical, these works have an innate balance, where the blank space emphasises the flow of the painted area. This is partly reflective of Daoist philosophy, which describes the natural flow of energy or qi, and the interaction between opposites. The blank areas are active sites, which create a feeling of infinity. These works seek to capture fleeting moments and elicit an emotional response to them, instead of being purely representational of the creature, landscape, or plant they may feature. There is a harmony between the spontaneity of the ink containing the innate flair of the maker, and the subject matter which is also full of vitality.

Drawing of Swallow and Lotus by Fachang Muqi 法常 牧谿 (mid-1200s)

Compositionally, it is interesting to consider the potential of open space in contrast to the previous examples which are visually full to the brim. The effect of opening space is one of serenity and contemplation, inviting the viewer to respond in their own way. This is unlike the previous examples that are designed to deliberately convey a narrative to the viewer. In my example drawing of Swallow and Lotus by Fachang Muqi we see a wonderful gust of air between the plants and the little bird soaring, with the work feeling like the embodiment of a deep breath. For me, I feel an immediate happiness for the freedom of the little bird, enjoying its soaring.

Diagonals and Swirls – Baroque Painting

The Baroque period encompasses a wide variety of artistic styles since it is the broad term for a huge amount of painting. This period spanned across countries, beginning around 1600 and continuing until around 1750. The grandiose, dramatic intensity, contrast in bright lights and deep shadows, and flurries of movement, characterise the Baroque period in general.

In architecture, this period manifested in adorning buildings with exceptional decoration. The classic trope being a floral churning of gold across every surface, underlining the power of the owners. The paintings existed within this realm too, and are hard to consider without also understanding the opulence of the decorated rooms they were created to inhabit. These works often contain a series of diagonals, sometimes forming diamonds or more complex shapes, and move with an underlying swirling motion. These lead the eye around the scene in a busier manner than the orderly triangles of the Renaissance, and lead us to a feeling of immediacy and action which is innately theatrical.

Drawing of Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi (1610)

Like the Renaissance, it’s hard to be selective from such a productive time, and no single work can represent the entire period, so I have chosen Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi to focus on. Here we see a series of diamonds in play, bouncing around the position of their limbs and heads whilst the brutal action takes place. We feel ourselves being twisted, and drawn into the image by the twisting of these shapes. I have picked out some of the diamonds in blue, with their overlapping arrangement intensifying the action of the image. If we contrast this with the relatively scattered triangles in The Birth of Venus, we can further see the emotional impact of the multilayered arrangement we see here.

Deconstructed Viewpoints – Cubist Painting

Cubism emerged in Paris in the early 20th Century through artists like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. In Cezanne’s late work, he depicted still life objects from slightly different viewpoints on the same canvas. The artists of Cubism evolved the idea further by shattering their compositions into fragmented planes. The effect of breaking the subject down and multiplying the viewpoints of it actually emphasised the flatness of the surface and made them exist within abstract space. This represented a landmark abandonment of linear perspective and representation that had dominated European painting since the Renaissance. And it planted the seed for movements that pushed abstraction further in the future. This deconstructed approach, with multiple planes at play, paired with an often muted palette, distills some of these works into pattern and geometry.

Drawing of Violin and Candlestick (1910) by Georges Braque

The example I chose to look at is Violin and Candlestick by Georges Braque, where we see the instrument splintered by an undulating cubed surface with the central candlestick anchored in the middle. There is no clear boundary between the objects that we are looking at since they are interlocking and overlapping, giving us no sense of a literal space. Yet our eye is still guided by the compositional choices made by the painter. The geometric shapes that dissect the work create a visual rhythm that we follow. I have highlighted this rhythm in green, from the bottom where the violin breaks out of the frame, up to the top of the work. Exposing compositional choice on the surface of the work, instead of disguising it within the imagery, lays it bare and allows us to think more about our experience of physical objects as we move around and beyond them, instead of a narrative or spirituality as we have considered before.

‘All-Over’ Effect – Abstract Expressionism

By prioritising the physical act of painting itself, mark-making and spontaneity were key to the Abstract Expressionists. They are defined by two different groupings within this movement – the action painters and the colour field painters. The key action painters were Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, who made large-scale work, with huge brushes, making sweeping gestures, and pouring and dripping paint onto the surface. The colour field painters can be exemplified by Mark Rohko’s work, where huge fields of colour fill the canvas, inviting the viewer to have a meditational, personal response to the work.

Drawing of Number 28 by Jackson Pollock (1950)

For this example, I’ve chosen an action painting since the composition is one of treating the entire surface with a shared intensity, with any gaps or breaks feeling incidental to the process rather than a conscious decision. This ‘all-over’ treatment of the composition can be seen in my drawing of Number 28 by Jackson Pollock. The compositional choice to completely free the work of any planes, structure, or inviting angles to enter the work through which our previous examples relied upon, makes the work confrontational and chaotic. There is a wildness and freedom that aligns with their aim to convey a reflection of the artist’s psyche, where the entire work becomes their signature.

The study of composition throughout art history reveals its essential role in engaging the viewer, as well as enhancing narrative and inducing emotion. By considering the compositions of the important works I drew my examples on, we gain insight into the process of the artists making them, and the individual historical context that led to their decisions. Compositional strategies have evolved alongside cultural shifts, reflecting artistic and philosophical evolution, with each movement having the privilege of reacting to and developing upon the past. Through the seven examples of composition that I selected from art history – which of course barely scratch the surface of this broad subject – it’s plain to see the breadth of possibility in this essential decision. From this knowledge, we can consciously adopt whichever strategies may improve our own works, and consider which effects we resonate with the most.

Further Reading

Tips for Creating Strong Composition and Illusory Depth

How to Resolve a Landscape Painting Composition

Jackson’s Inaugural Plein Air Painting Day

Inside the Sketchbook of Evie Hatch

Shop Art Materials on jacksonsart.com

Trending Products